|

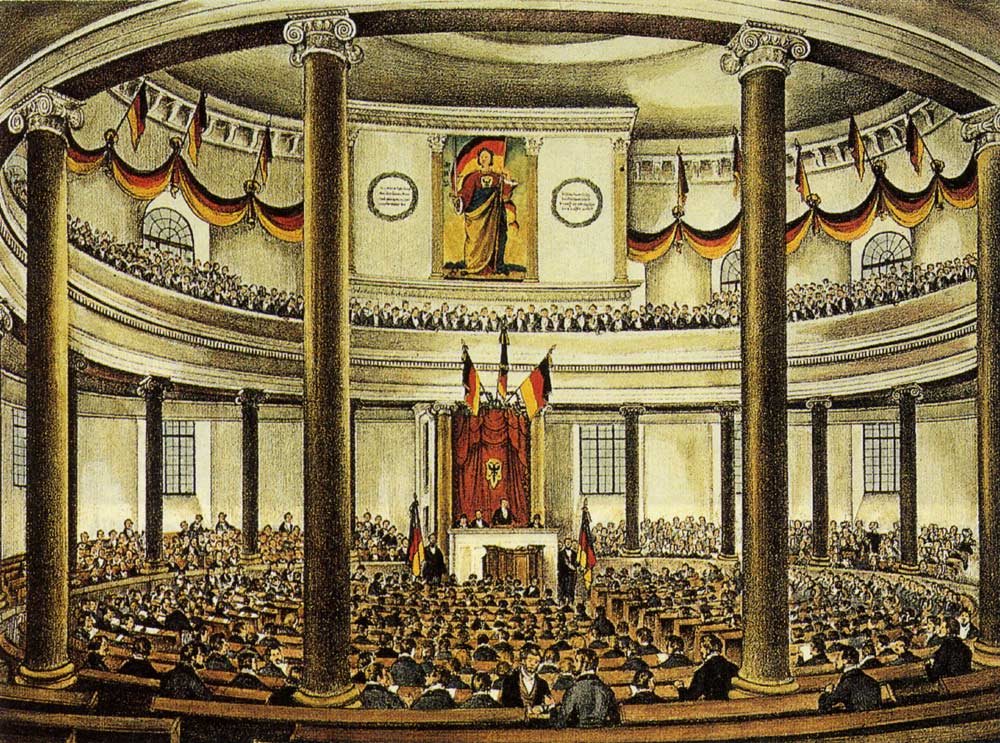

| German National Assembly during the March Government responding to the March Demands |

In terms of economic growth, as the need “to fear political upheavals. . . in the aftermath of the revolution” subsided, “much group work had been laid for industrial development (Schulze, 130). The people of the German nation began to expand and take advantage of “a golden era for entrepreneurship” (Schulze, 130). Facilitated by the social freedoms demanded and generally established, new banks and factories were opened. One essential task that the banks provided capital for was the creation of railroads, inspired by economist Friedrich List (Schulze, 130). This transportation network was essential to unify “this new and relatively large economic bloc” that the German nation was entering into (Schulze, 130). “Labor was cheap,” which also spurred this growth, elevating the status of the “preindustrial masses” (Schulze, 131). As Schulze profoundly states, “Industrialization (encouraged by renewed social and literal mobility) transformed German society. The old world disappeared not as a result of a political revolution but through a revolution in the economy and the world of labor” (Schulze, 132).

However, as social mobility and freedom had the potential to uplift the liberal bourgeoisie, this dramatic shift in industry instilled a feeling of “uprootedness” (Schulze, 134). As Schulze further describes, “Family ties were broken, traditional loyalties abandoned, religious attachments weakened” (Schulze, 134). This fundamental shaking of society’s orientation caused an “identity crisis,” though growth, philosophy, and liberalism great through adherence secular ideologies, contributing to the rise of the German state (Schulze, 134-135). Starting as a backward country seeking nationhood, Germany needed to promote social and economic growth, especially when considering the thought of Friedrich List, an economist referred to briefly in the text. List believed personal factors, the work of the people, led to growth and that individuals, empowered with freedom, can spur industry. Through their attempts at constitutional reform, including profound suggestions toward liberty, and their industrial successes, albeit leading to identity crisis, were not completely successful, the German nation moved towards unification, surpassing challenges of growth during this tumultuous era.

|

| First Railroad station in Germany (clearly updated) The Growth of railroads furthered the growth of industry during this time |

No comments:

Post a Comment